On this day in 1942, the Royal Navy attempted to stop a breakout by the core of Hitler's Navy from Brest to Germany - the 'Channel Dash', a date which has entered Fleet Air Arm history.

With its vast natural harbour – 70 square miles in all, formed by the convergence of three rivers – and easy access to the Atlantic via the narrow strait, the Goulet, the Breton city of Brest had been a vital naval base since the days of Cardinal Richelieu, home first to the La Royale, and later Marine nationale.

In the summer of 1940, came a new inhabitant: the Kriegsmarine, which regarded the port as its greatest prize when France fell to the seemingly-unstoppable German Army.

No longer did the great ships of the German Navy have to run the gauntlet of the North Sea between the Shetlands and Norway, or the Iceland Gap. From the Atlantic shores of France, they could strike at the supply lines of the British Empire.

Or at least that was how the leaders of the German Navy viewed the ports of France in the summer of 1940. The reality proved to be very different – for the German surface fleet especially.

Brest in particular became not a sword lunging into the Atlantic but a sanctuary for German warships escaping the clutches of the Royal Navy.

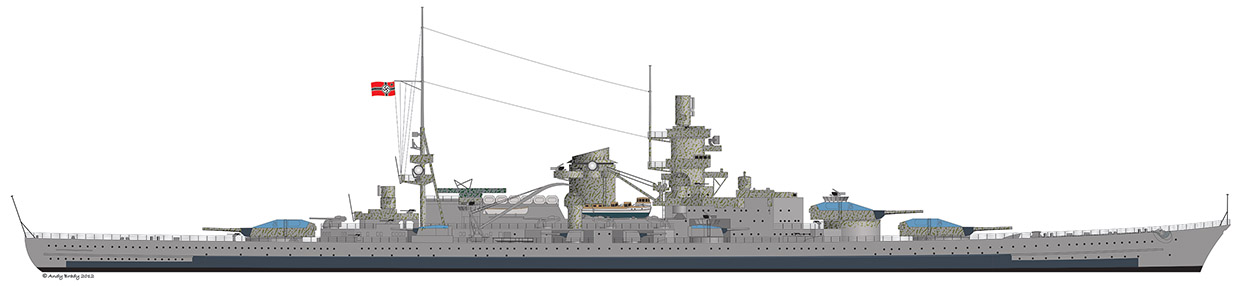

It was to Brest that the sisters Scharnhorst and Gneisenau – the British determined the 38,000-ton leviathans with their nine 11in guns apiece were battle-cruisers, the Germans insisted they were Schlachtschiffe, battleships – had fled after a two-month-long sortie in early 1941.

It was for Brest that the damaged Bismarck made in May that year. The torpedo of one Swordfish bomber and the guns of the Home Fleet ensured she never got there – but her escorting heavy cruiser, Prinz Eugen, did reach Brittany.

As sanctuaries go, Brest proved to be a poor one. It was barely 120 miles from the shores of England – well within striking distance of the RAF.

Within eight days of their arrival in Brest, British bombers targeted the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.

The Fleet Air Arm had already damaged Gneisenau as she returned from her sortie. Now the RAF compounded her agony. She was almost sunk by a torpedo strike which earned the pilot, Kenneth Campbell, a posthumous Victoria Cross. Yet more damage was inflicted on the wounded leviathan a few days later.

The Scharnhorst survived these raids unscathed – but she was hardly fit for sea, dogged by engineering problems which had hampered her sortie early in 1941 and continued to plague her.

It was July 1941 before das glückhafte Schiff – ‘the lucky ship’, a nickname applied not just to Scharnhorst but also the Prinz Eugen and the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer – was able to put to sea once more. After brief trials in the roadstead off Brest, she sailed 200 miles down the coast to La Pallice. Thanks to the French underground resistance, it took the RAF just a day to find her. Five bombs pierced her armoured deck, but only two exploded; the rest simply punched straight through the hull. She returned to Brest – shipping 7,000 tons of Atlantic seawater – and underwent four months of repairs.

By then the two sisters had been joined by a third heavy ship, the Prinz Eugen. She had sailed into the commercial port of Brest on the afternoon of June 1.

While the Iron Cross was presented to around one fifth of her ship’s company, the 680ft ship was covered with camouflaged netting.

She was spared the RAF’s attention for a month – until the small hours of July 2 when a bomb pierced her armoured deck and exploded deep inside, killing or fatally wounding 60 men and putting the cruiser out of action for three months.

While Prinz Eugen was repaired, many of the ship’s company enjoyed leave. Some headed to Locquirec on the north Brittany coast for training as soldiers, others were sent on promotion courses. There were ceremonial days celebrating the deeds of the man for whom the ship was named, Prince Eugene of Savoy, the great 17th and 18th Century commander of the Habsburg armies, scourge of the French and Turks. There were more air raids – 21 sailors were wounded while rescuing Frenchmen buried alive during one attack on Brest – and other dangers in the city. Sailors came under attack from armed members of the French resistance, leading to a ban on officers leaving the ship without pistols. Welders set fire to the camouflage netting which shielded the cruiser from Allied aerial reconnaissance.

Elaborate nets were also spread over the two battle-cruisers – from the air they supposedly looked like clusters of trees – while the obsolete French cruiser Jeanne d’Arc was made to look like the Scharnhorst.

Kriegsmarine commanders determined the defence of Brest should be “as important as the defence of Wilhelmshaven”. The port was ringed by smoke generators and more than 1,300 anti-aircraft guns, while the naval base and docks were ingeniously camouflaged.

Such deception proved largely futile. Aerial photographs of Brest in the autumn of 1941 – more than 700 reconnaissance flights were flown – show the unmistakeable outline of the two sisters in dry dock and the Prinz Eugen alongside a little further to the west.

Royal Air Force ‘visits’ to Brest were an almost daily – and nightly – occurrence. Roughly ten per cent of Bomber Command’s effort was expended attacking the German warships in western France. The RAF made just shy of 300 attacks on the three heavy warships – at a cost of more than 40 aircraft and nearly 250 aircrew.

And yet despite the damage British bombs inflicted on the trio, the air attacks couldn’t deliver the knockout blow. There were plans to throw 300 aircraft at Brest in a single night, a seemingly-endless wave of bombers raining high explosive on the ships.

There never was such a raid. Instead, the RAF persisted with its smaller-scale attacks on the French port, succeeding in damaging Gneisenau once again on January 6. The damage was relatively minor – a couple of compartments flooded. She would be ready to sail again on February 11.

By then the Prinz Eugen and Scharnhorst had also been repaired and were ready for duties. But where?

The 'lucky' Scharnhorst

The answer was Norway. Long before commandos had struck at Vaagsoy, Adolf Hitler had been convinced the British would strike at Scandinavia.

To the German leader, Norway was a Schicksalszone – ‘zone of destiny’ – to be safeguarded at all costs. Germany had struck north in the spring of 1940 – at the insistence of the Navy, overlooking the small matter of Norwegian independence – to secure iron ore supplies through Narvik.

But in seizing Norway, the Kriegsmarine had sacrificed much of its surface fleet. It didn’t have the forces to protect the 1,200-mile sea lane from Narvik to the North Sea coast of the Reich. It certainly didn’t have sufficient forces to guard more than 15,000 miles of Norwegian coastline. To prove the point British ships, submarines and aircraft were striking at German shipping off the Norwegian coast – if not at will, then certainly regularly.

The Kriegsmarine’s commander, Erich Raeder, and his fellow admirals shared Hitler’s fears. Indeed, his commander in Norway, Admiral Hermann Boehm, went so far as to warn that Norway was a “pistol aimed at England’s heart” – and they would do everything in their power to knock it out of Germany’s hand, while his counterpart commanding the Kriegsmarine’s North Sea commander Admiral Rolf Carls warned that the Allies would strike inside the Arctic Circle around the beginning of April.

Such ‘threats’, plus the growing convoy traffic between Britain and the Soviet Union had already prompted Raeder to bolster his meagre forces in Norway; he would send the new battleship Tirpitz to Trondheim when she had completed her training.

That reinforcement wasn’t enough for Adolf Hitler. “If the British do things properly, they’ll attack northern Norway in several places,” he assured Raeder. There would be an “all-out assault” by the Royal Navy to seize Narvik which could be “of decisive importance for the outcome of the war”. The ‘threat’ to Norway demanded the “use of all the Kriegsmarine’s forces – all battleships and pocket battleships” and that meant transferring the three ships in Brest.

The ‘fleet in being’ at Brest served no purpose, Hitler argued. They were like a patient with cancer – “doomed without an operation”. The operation he proposed was a breakout through the Channel – based on past experience the English were “incapable of taking and carrying out lightning decisions”. It was a gamble, but he pointed out to his naval commander: “An operation, even if it’s a drastic one, offers at least some hope of saving the patient’s life.”

Erich Raeder did not baulk at the idea of abandoning Brest – even he conceded that it was not a suitable base for his ships. But he did baulk at the prospect of withdrawing his ships to home waters, for abandoning the Atlantic coast was tantamount to abandoning the war at sea – with the big ships at any rate.

But it went beyond simply abandoning the guerre de course for which he had built his fleet over the past 14 years. The loss of the Bismarck – and more recently the sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse – confirmed to Adolf Hitler that battleships “have had their day”. Perhaps they would be sent to Norway – but there was every chance that they might also be broken up, their guns mounted ashore and their crews sent to U-boats.

Such ‘ifs’ were, of course, dependent on the biggest if of all: if the ships reach Germany safely.

Secrecy and surprise were fundamental to the success of Operation Cerberus, as the breakout would be codenamed. The ships would leave Brest at night to avoid being detected by British air and naval forces, and charge up the Channel, passing Dover in daylight.

But were the ships up to such a dash? Erich Raeder doubted it. With their ships being laid up so long, crews were rusty. They needed training – and training at sea at that.

No, said Hitler – who knew little, if anything, of life at sea. If the ships began training, the British would soon be alerted through their extensive network of spies. That could only lead to more air raids and the three heavy ships would be damaged once again.

“The only possibility is a surprise breakthrough with no previous indications that it is to take place,” Hitler insisted.

There was another prerequisite: air cover. The ships needed an aerial umbrella from daylight – somewhere off the Cotentin peninsula – to nightfall, off the Rhine estuary.

The Luftwaffe could provide such an umbrella – Operation Donnerkeil (Thunderbolt) – but even by committing every available fighter in France and Germany, some 250 Messerschmitt 109s, twin-engined long-range Messerschmitt 110s and the new Focke-Wulf 190s – it could not guarantee round-the-clock cover.

Germany’s senior fighter pilot, the cigar-loving Adolf Galland, promised his men would “give their all – they know what is at stake”. But he could not promise success. “We need total surprise – and a bit of luck to boot.” Adolf Hitler took the fighter pilot to one side. “Most of my decisions have been bold,” he told Galland. “Only those who accept the dangers deserve luck.”

A Swordfish drops a torpedo

Long before Adolf Hitler decided on a breakout through the Channel, the Admiralty had suspected he might take such a gamble. Over the winter of 1941-42, there had been growing intelligence to suggest the Brest surface ships were being readied for action: gunnery crews were being sent to the Baltic for training while the vessels themselves were making short forays from Brest to work-up. They might lunge once again into the Atlantic to strike at Britain’s supply lines – but the Admiralty thought it more likely that the trio would “break eastwards up the Channel and so to their home ports”. They would, of course, have to be stopped.

But in the Channel, the most powerful navy in Europe had little to challenge the three German heavy ships – and certainly nothing gun for gun. Plymouth, Portsmouth, Portland and Chatham all proved every bit as vulnerable as Brest to aerial attack.

That vulnerability, compounded by the Royal Navy’s global mission – the Battle of the Atlantic, Russian convoys, the struggle in the Mediterranean and the new and terrible conflict in the Far East – left Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay, the senior naval officer at Dover, with meagre forces to halt any breakout: half a dozen destroyers and a similar number of torpedo boats.

Ramsay, architect of the Dunkirk evacuation, could call upon the forces of the RAF – Fighter, Bomber and Coastal Command – and half a dozen Fleet Air Arm Swordfish torpedo bombers, to be transferred to RAF Manston near Ramsgate.

And that was pretty much all that was allocated to Operation Fuller, the yang to Cerberus’ yin.

Still, Ramsay and his staff set about planning to stop the Germans. The motor boats and Swordfish would launch a co-ordinated attack to cripple the ships, destroyers would then close in to deal further blows, while the RAF would rain bombs from above, protected by a shield of fighters.

Success – or failure – depended on forewarning. Staff officers studied the charts and concluded that the moon and tide favourable for a breakout suggested the Germans would strike any day from February 10 onwards. They made just one error in their calculations. The Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen, intelligence assessments agreed, would use the shield of night to hide their passage through the Strait of Dover.

Lt Cd Eugene Esmonde (second left) pictured on HMS Ark Royal with other FAA aviators decorated for the Bismarck chase

At HMS Daedalus by the northern shore of the Solent, 825 Naval Air Squadron was still in the process of re-forming.

It numbered just six antiquated Swordfish torpedo bombers with crew – pilot, observer and telegraphist/air gunner for each aircraft – and a small number of engineers.

Just a couple of months before, the squadron had been flying from HMS Ark Royal, until a German torpedo sank the legendary carrier in the Mediterranean – and took several of 825’s Swordfish down with her.

The re-constituted squadron would take at least a month to train, perhaps two. But when volunteers were sought for a special unit to attack the German Fleet, Lt Cdr Eugene Esmonde stepped forward and offered 825.

His comrades weren’t “particularly happy” at the prospect, recalled observer Edgar Lee. But they took comfort in the fact that Esmonde was a hugely experienced pilot – and that they would strike at the Hun ships by night and the Swordfish was a very good night-time torpedo bomber. “We never envisaged in our worst nightmares that we would be asked to attack a fleet in daylight with enormous air cover,” the 20-year-old observer said.

On February 4 1942, the Swordfish of 825 Naval Air Squadron began to arrive at Manston in a snowstorm. From then on, whenever conditions permitted – “the weather was terrible, snow, very cold, bitter days,” Edgar Lee remembered 65 years later – the inexperienced squadron practised patrols in the dark. “With the protection of darkness the Swordfish will have a chance of delivering their attacks and getting away,” a staff officer assured the naval aviators. But it would, he conceded, “be pretty fierce when it starts.”

For two days HMS Sealion had lurked in the waters off Brest. Hurriedly dispatched from Gosport to stand guard off Brittany in case the Germans should emerge, the submarine had fought against the strong tides ripping from Biscay to the Channel through the narrows between Brest and the Finistère archipelago. For despite Hitler’s instructions to the contrary, the Brest warships were making sporadic forays outside the safety of the port to conduct trials and exercises. News reached British shores.

So far Sealion’s patrol had proved fruitless: no sign of the German trio. The boat moved to the edge of the channel leading out of Brest harbour in the hope of finding richer pickings. After dark on February 9, the submarine surfaced in the hope of catching the Germans sailing.

The ships did not come. But a Luftwaffe Do217 bomber did, sweeping over the bay on a routine patrol. Sealion dived – but the game was up. She was subjected to depth charge attack, rocking but not damaging the boat. It was clear to her captain that the waters off Brest were unsafe. He took Sealion further out to sea.

The next day Adolf Galland’s fighters completed their final sweep of the Channel. On eight days between January 22 and February 10, he sent his aircraft aloft – not too many to arouse British suspicions, but enough to prove that the aerial umbrella would work. His pilots knew nothing of their missions – these were just routine patrols.

With the Donnerkeil practices complete, Galland was summoned to the Palais du Luxembourg, the Luftwaffe’s sumptuous French headquarters in the heart of Paris. The weather forecast for the next day, Thursday February 12, was far from encouraging, for flying especially – worsening through much of the hours of daylight until a front passed – but the Navy decided that Cerberus should begin that night, passing through the Channel on the 12th. It could, of course, postpone the breakout by 24 hours... but superstitious sailors did not relish the prospect of carrying out the operation on Friday 13.

From Paris, Galland flew to the Pas de Calais to brief his front-line fighter commanders on the breakout and handed them sealed envelopes containing detailed instructions for Donnerkeil. News of the mission “hit them like a bomb”, but despite the surprise, they voiced their enthusiasm for the mission.

While Adolf Galland was briefing his commanders, Joseph Goebbels was closeted with Hitler in the gaudy but imposing Reich Chancellery in Berlin’s government quarter. The Propaganda Minister found his Führer rather unsettled; he had returned to the German capital for the state funeral of his friend and engineer Fritz Todt, killed three days earlier in a mysterious plane crash.

Todt’s death “has badly shaken him”, the Propaganda Minister observed. Also weighing on Hitler’s mind was the impending breakout by his warships at Brest. “We’re all shaking in case something happens to them,” Goebbels recorded in his voluminous diary. “It would be dreadful if one of these ships were to suffer the same fate as the Bismarck.”

After a week of trying to bring his scratch squadron up to operational status, Eugene Esmonde had been given the day off to go to London.

The 32-year-old had more than a dozen years’ flying experience under his belt: five in the RAF, a similar number as a civilian pilot for Imperial Airways before donning uniform once more on the eve of war, this time in the fledgling Fleet Air Arm.

Esmonde knew what it meant to lead obsolete Swordfish against German capital ships; he had guided the torpedo bombers of 825 squadron against the Bismarck eight months previously. He had done so in the dark, in foul weather, and in the face of ferocious flak – and he had scored a hit; a torpedo struck Hitler’s flagship.

For his actions that night, Esmonde was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. This Wednesday he would receive his medal from George VI at Buckingham Palace.

In Brest, the captains of the Prinz Eugen and Gneisenau joined their counterpart from the Scharnhorst in the admiral’s cabin on the flagship. It had fallen to Otto Ciliax to lead the three ships up the Channel – although he had little belief in the mission, less still the reasons for abandoning the Atlantic coast.

The 50-year-old admiral, Befehlshaber der Schlachtschiffe (Commander of Battleships), was not an especially popular leader – a rather dour figure known by some as the Der schwarze Zar (Black Tsar). Ciliax was a stern disciplinarian who expected his orders to be followed to the letter. This counted more than ever now, he told Otto Fein of the Gneisenau, Helmuth Brinkmann of the Prinz Eugen, and his own flag captain, Kurt Hoffmann.

“It is a bold and unheard of operation for the German Navy,” Ciliax impressed upon them. “It will succeed if these orders are strictly obeyed.”

Beyond the narrowest circle, the crews of the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen knew nothing of their impending charge up the Channel. They believed they were heading south, not north – pith helmets and barrels of lubricating oil were being stored aboard. Nor did they believe their departure from Brest imminent. Preparations for one of the most important dates in the German calendar, Shrove Monday – on February 16 – were in full swing. It would be celebrated in the traditional manner – with a costume party ashore. More pressing for the ships’ officers were two days in Paris as guests of Admiral Alfred Saalwächter, the Kriegsmarine’s commander in France. Lists were circulated with the names of officers who were to attend a dinner with Saalwächter, followed by a day’s hunting in Rambouillet on the edge of the French capital.

At 7pm the alarms sounded aboard the Prinz Eugen. Seeklarmachen. Ready for sea. Gun crews manned their turrets while a tug was brought alongside to shepherd the cruiser out of harbour.

She would be the last of the three ships to sail. Scharnhorst, as flagship, would lead, followed by her sister, then the Prinz. Once in open water, they would sail in Kielwasserlinie – in line astern – with a protective shield of half a dozen destroyers, more than a dozen torpedo boats, and fast patrol craft – S-boats to the Germans, E-boats to the British.

In half an hour, the force was ready to sail. But suddenly the alarms sounded once more: air raid. For the next 30 minutes the sailors waited tensely, while smoke screens billowed across the harbour. Five parachute flares lit up the entrance to the port. But the handful of bombs dropped by the Wellingtons fell over the city, not the harbour.

It was another hour before the all-clear sounded – and 15 minutes more before the red lamp on Scharnhorst’s bridge flickered through the gloom.

A B L E G E N. Cast off. It took another hour to clear the narrow entrances to Brest. By 10.30pm, the tugs had done their duty and turned about.

On the bridge of the Scharnhorst, Officer of the Watch Kapitänleutnant Wilhelm Wolf asked the ship’s navigator for the course to steer. “Steuerbord drei vier null,” Helmuth Gießler told him. Turn starboard to 340 degrees. Wolf queried the course – it would take the ships out into the Channel. “The course is correct,” Gießler grinned. “Tomorrow you’ll be at home with your wife.”

The rest of Scharnhorst’s crew still knew nothing of their mission – or their destination. Only a little after midnight – as the force cleared the narrow and hazardous waters between Ushant and the Brittany peninsula and increased speed to 27 knots – did the loudspeakers come to life. They broadcast Otto Ciliax’s order of the day. “The Führer has summoned us to new tasks in other waters,” he told them. The force was to sail east through the Channel to the German Bight – a difficult mission, one which demanded a supreme effort from every man. “The Führer expects from each of us unwavering duty. It is our duty as warriors and seamen to fulfil these expectations.”

Each night a handful of Hudson bombers of Coastal Command patrolled the skies from the Pas de Calais to the tip of the Brittany peninsula, using their radar to sweep the Atlantic and Channel for movement. Tonight was no exception.

Except that tonight was an exception. For the radar on the first Hudson failed mid-Channel. It returned to base in St Eval on the north Cornish coast. By the time a replacement arrived off Brest, Ciliax was gone.

A second Hudson, due to scour the waters between Ushant and Brest fared no better. Its radar failed. It too turned for home – 90 minutes before Ciliax sailed. No replacement was sent.

In a hotel near Versailles, a bleary-eyed Oberleutnant Gerhard Krumbholz had been summoned to the telephone to take a call from his commander. The Luftwaffe observer had barely returned from a lengthy reconnaissance flight in a Junkers 88 bomber over the English south coast, grabbed some food and retired to bed.

Still dressed in his pyjamas, Krumbholz took down some coded instructions, woke his three other crew members then sat down to decipher the message: before first light they would be over the Channel once more, this time providing cover for the breakout of the battleships.

At least the radar on a third RAF reconnaissance aircraft was functioning. So far this night it had completed two sweeps of the Channel between Boulogne and Le Havre. Nothing. It would have made a third, but with the weather closing in on its base, it was recalled early. At 6.15am on Thursday February 12, it set course for Thorney Island.

Adolf Galland had slept little. A good 90 minutes before dawn he had opened his aerial umbrella, sending night fighters over the warships. The Me110s flew just a few feet above the waves to avoid being picked up by British radar stations across the Channel.

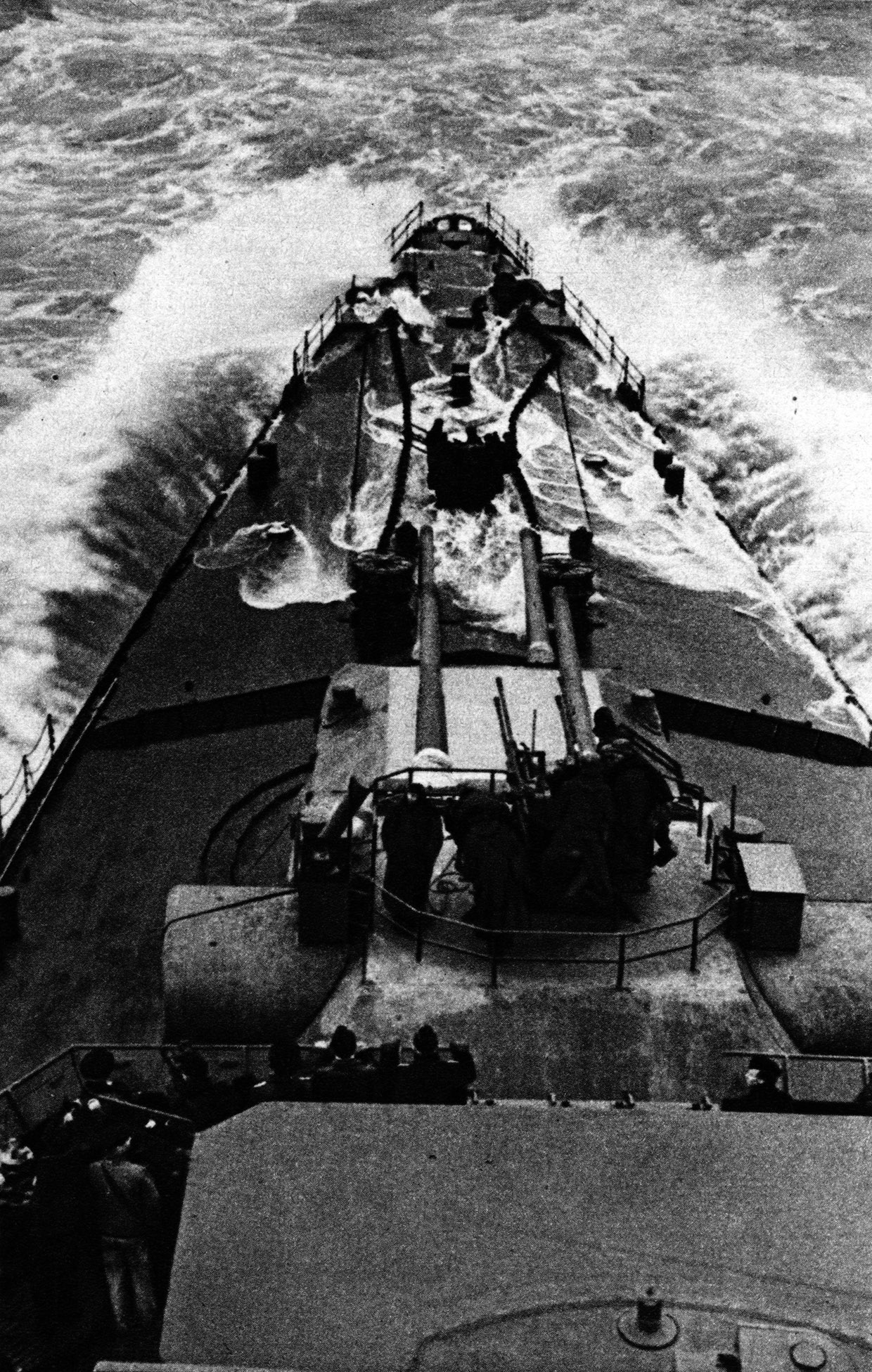

A grainy image of the Scharnhorst crashing through the Channel on February 12 1942

Aboard the Prinz Eugen, individual sailors were released from their action stations to grab food from the galley or to enjoy a cigarette.

On the cruiser’s bridge, Kapitänleutnant Paul Schmalenbach stared into the half light of a dawning February day. He watched as the screen of destroyers formed a ring around the three capital ships. They were soon joined by torpedo boats and then, as the day lightened, Me109s, the twin-engined Me110s and Focke Wulf 190s. Long before they roared over the ships, their recognition signals blinked reassuringly in the gloomy sky.

At Parkestone Quay in Harwich, the ships of the 16th Destroyer Flotilla slipped their moorings and headed into the North Sea. It promised to be a routine, if useful, day of training: a spot of practice with their 4.7in and 4in guns against a towed target

Gerhard Krumbholz was still trying to locate the task force. His Junkers 88 had taken off before dawn and headed north for the Channel. “Apart from the shifting sea and the blue, almost cloudless sky above it, there is nothing to see,” he wrote.

Also airborne in the skies of the Channel that morning were a pair of Heinkel 111 bombers – specially fitted with jamming equipment to fool the radar stations dotted along the south coast of England. To the operators of the sets, on the cathode ray screens the two Heinkels looked like 50 aircraft.

The flight by the two bombers was just one part of an elaborate deception mission to block and obfuscate the British this day. Land-based devices joined in.

For the most part it succeeded. The RAF stations reported interference, or simply switched off. But not all – some broadcast at frequencies the Germans could not block. And not everything could be hidden.

For as the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen moved, their umbrella moved with them, flying constantly in circles to maintain contact with the ships – and there was no hiding Galland’s flying circus as it barrelled its way up the Channel.

At first these movements had been dismissed as training exercises, or perhaps a large-scale fighter sweep. But by mid-morning there were some operators and staff officers who began to suspect German ships were on the move. The RAF ordered a handful of Spitfires up to take a look.

Unteroffizier Willi Quante, in a Messerschmitt 109, was on his second sortie of the day. His first flight – to Dover and back – had passed “without detecting anything worth reporting”. His second mission was proving to be equally uneventful. “Outside of five German destroyers, acting as a forward screen, we detected no other activity.”

Gerhard Krumbholz’s bomber has now been airborne for well over two hours. Nothing. No German aircraft. No Tommies. In the air or on the sea. But shortly before 10am Krumbholz and his crew spied three smoke trails in front of them, silhouetted against the weak February sun. There was, Krumbholz recalled, “jubilation on board” at the sight of the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen. He continued:

Majestically and calmly they move through the turbulent sea, surrounded by numerous security vessels, destroyers and minesweepers. Motor torpedo boats hunt protectively on all sides. Often the boats nearly disappear in the heavy breakers. German fighter planes circle over the naval unit heading for the narrow Channel. The hearts of the four comrades beat faster.

Never before had Germany’s power at sea and in the air been as clear and present for them as it was today. They could hardly get enough of looking at this glorious picture full of strength and greatness.

Having located the formation, the Junkers changed course and headed for the South Coast of England. Nothing. “The Tommies,” wrote Krumbholz, “appear to be asleep.”

In his command post at Le Touquet on the Channel coast, Adolf Galland had reached the same conclusion. “For two hours – in broad daylight – German warships had been sailing along the English coast along a route no foe had dared take since the 17th Century. The silence was almost sinister.”

The sleeping giant was about to awaken... but it did so lethargically.

The Channel crashes over the bow of the Prinz Eugen

The first concrete proof that ‘something was up’ in the Channel was provided by blips on a coastal radar screen which picked up a concentration of ships roughly two dozen miles off Hastings.

Five minutes later, the first RAF reconnaissance aircraft sighted the naval formation – but failed to identify them. It was 11.05am before the German breakout was confirmed... but maintaining radio silence – as per orders – it was only when the Spitfire which found the ships was on the ground, at 11.09, that the slow wheels of Operation Fuller began to turn.

The initial response was far from impressive. It was almost 11.30 by the time the information filtered down to the one sailor who could stop the breakout. The news came – with typical Royal Navy understatement – as “an unplesant surprise” to Bertram Ramsay.

Ramsay would do all he could – but he was reluctant to throw half a dozen biplanes against the German ships by day, however much fighter cover the Royal Air Force could provide. Ramsay rang the First Sea Lord for advice.

The instructions of Admiral Sir Dudley Pound were unequivocal:

The Navy will attack the enemy whenever and wherever he is to be found.

At RAF Manston, the station commander handed Eugene Esmonde the telephone. First Ramsay’s aerial liaison officer spoke to the Swordfish commander. Then Admiral Ramsay himself came on the line: “This is going to be a difficult job,” he told Esmonde. “You volunteered for a night attack, it’s now a daylight attack. It’s up to you. I shall not think any less of you if you withdraw.”

Eugene Esmonde felt a bounden duty to attack the German force. He laid down only one condition: fighter cover. The RAF promised five squadrons to protect his sluggish bombers. “Tell them to be here by 12.25 – get the fighters to us on time, for the love of God.”

Even with fighter cover, Esmonde felt this was a one-way mission. He never voiced his misgivings – but his half-hearted salute to Manston’s commander, Tom Gleave, as the RAF man wished him luck spoke volumes.

He knew what he was going into [wrote Gleave]. But it was his duty. His face was tense and white. It was the face of a man already dead. It shocked me as nothing has done since.

As Eugene Esmonde and his men donned Mae Wests and headed out to their Swordfish, the other pieces of Operation Fuller were slotting into place.

Shortly after mid-day the coastal batteries along the Kent coast cleared their throats. They were not firing blind – they were firing at targets guided by their radar. But they were firing at maximum range – 20 miles. It took nearly a minute for the 9.2in shells to travel from their barrels at South Foreland, four miles up the coast from Dover. For the next half hour the guns fired spasmodically, sending more than 30 shells into the Channel sky... and plunging harmlessly into the sea.

Waves crash over the bow of the Prinz Eugen

Heading “flat out” of Dover Harbour, Lt Cdr Nigel Pumphrey tried to shepherd his five motor torpedo boats. He should have had six, but one failed to start and remained behind in what had been the ferry dock before the war.

Pumphrey’s mission was as thankless as Eugene Esmonde’s. His boats were old, slower than the German capital ships – to say nothing of the escorting E-boats. The weather in the Channel – winds upwards of Force 6 and waves easily of five or six feet – was beyond the motor boats’ operating limits. As for actually attacking the foe, the torpedoes were not supposed to be fired above a Force 3.

At 12.25pm precisely, six Swordfish – codenamed F, G, H, K, L and M – with 18 souls – one pilot, one observer and one telegraphist air gunner apiece – lumbered into the Kentish sky and sluggishly climbed to 1,500 feet where they circled for four minutes awaiting the five RAF squadrons.

Only one appeared. Ten aircraft. Spitfires. The other four squadrons failed to materialise. With time pressing, Esmonde signalled the other five torpedo bombers. They set an easterly course and struck out over the Channel, dropping to 50ft. They expected to run into the German warships two dozen miles east of Ramsgate.

Beneath “grey and scudding clouds” telegraphist Reg Mitchell and his shipmates on MTB 48 saw the Swordfish pass overhead – at the very moment the German Fleet came into view. At that very moment Mitchell’s radio gave up, a fact he reported to his skipper, Tony Law. “Come up top and grab a rifle or something,” Law advised.

The escorting Spitfires of 72 Squadron were struggling to provide cover for the plodding torpedo bombers and weaved constantly to prevent losing contact.

The weaving was of little use. Fifteen – or maybe 20 – Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs dived out of the clouds, past the Spitfires and pounced on the tails of all six Swordfish, damaging at least three of the biplanes.

From MTB 48, Reg Mitchell could clearly see the German fighters with their landing gear down and flaps extended, and he could hear the pilots gunning their engines to prevent stalling – and prevent them overshooting the Swordfish. To Mitchell it seemed the Germans “were queuing up to get a shot at them”.

Whilst trying to keep the Focke-Wulfs and Messerschmitts at bay, Spitfire pilot Michael Crombie’s eye was caught by Esmonde’s bomber fending off repeated waves of attacks, its gunner PO William ‘Clints’ Clinton responding to the 20mm cannon of the German fighters with his much-less-potent Lewis machine-gun. When tracer set the tailplane alight, the senior rating left his cockpit and clambered along the fuselage to beat the flames out before returning to his seat to continue the struggle against the foe.

For seven or eight minutes, all six Swordfish came under sustained attack – and yet all six were still airborne. Perhaps they might succeed. They pressed on and when the German warships came into sight, Esmonde turned towards them.

A grainy photograph of the Luftwaffe and patrol boat escort for the Channel Dash

A couple of Me109s buzzed Reg Mitchell’s torpedo boat. They were barely 40ft above the water – low enough for the 18-year-old to clearly see the German pilots. They grinned at the crew of MTB48 – but didn’t open fire. “They obviously all thought we were pathetic and insignificant,” Mitchell recalled.

Through the loudspeakers of the Prinz Eugen a tinny voice: Aircraft, bearing 240 degrees, four low-flying aircraft, biplanes, torpedo bombers! The broadcast, Paul Schmalenbach recalled, “electrified” the cruiser’s crew.

On the bridge of the Scharnhorst, Otto Ciliax was unperturbed. “The English are now throwing their mothball navy at us,” he observed acidly

In aircraft ‘G’, observer Edgar Lee watched as the anti-aircraft – or flak – guns on the escorting forces opened fire. The guns did not belch with full fury, however, for fear of hitting their own fighters.

Even with subdued fury, the German fire was fearful. The lower left wing of Esmonde’s Swordfish was all but shot away, his gunner dead, the canvas on the fuselage torn away, yet the rugged bomber flew on. It closed to within 3,000 yards – a little over one and a half miles – of the heavy ships.

It got no further. It plunged into the Channel. Edgar Lee thought it was shot down by a fighter. Prinz Eugen’s flak gunners were convinced they had downed the Swordfish. Nor is there agreement over whether Esmonde launched his torpedo. If he did, it failed to find a target.

Swordfish ‘G’ and ‘L’, following Esmonde, faired little better. L flew so low that bullets ricocheted off the waves and peppered the fuselage. Part of the upper wing caught fire, two engine cylinders were shot away, so too the floor beneath gunner Don Bunce who was forced to brace himself against the fuselage to avoid falling into the Channel. As for L’s pilot, S/Lt Pat Kingsmill was shot in the back, his observer ‘Mac’ Samples was also wounded.

Once again the Swordfish demonstrated its legendary ability to take punishment. It flew on. Bunce brought down at least one German fighter while Kingsmill turned the bomber 360 degrees to evade the Luftwaffe before bringing his aircraft to bear on the Prinz Eugen.

There is no dispute about Kingsmill’s torpedo. It launched and passed just astern of the heavy cruiser which moved violently as it took evasive action.

As for the aircraft, it turned for home but would never get there. Another hit detonated the aircraft’s distress flares and possibly wrecked the dinghy. With no hope of returning to base, Kingsmill sought to ditch. He was just about to do so when he realised the motor boats swarming just a few hundred yards away were German, not British. He continued until the Bristol Pegasus engine finally gave up then set the Swordfish down in the sea. The three crew spent ten minutes in the water before a British MTB rescued them.

Swordfish ‘G’ had also got its torpedo away after an equally horrific run-in. Pilot Brian Rose was badly wounded in the back. He and observer Edgar Lee were badly affected by fumes from the punctured fuel tank. At around 2,000 yards from the main German force, Rose released his torpedo, probably at the Gneisenau, observed its run briefly, then turned. The aircraft passed over the outer screen of destroyers but got no further, crashing into the sea. Lee freed himself, then the badly-injured Rose, helping the pilot into the dinghy. He could do nothing for gunner Ambrose Johnson, slumped over his gun and trapped in his seat. The Channel swallowed the Swordfish whole, taking Johnson with it.

A Swordfish disintegrates off Prinz Eugen's port side

The fate of the remaining three torpedo bombers is even more bleak. Lee last saw the three aircraft pressing home their attack on the Prinz Eugen, jinking wildly to avoid the flak. All three were shot out of the sky. Not one man survived and only one body was ever recovered.

Thus ended the Fleet Air Arm’s ‘Charge of the Light Brigade’. It achieved nothing, save to add a bitter but brave chapter to the annals of naval aviation. Having brushed aside the ‘mothball navy’ just minutes before, the icy Otto Ciliax reflected on the attack. The “handful of ancient planes” had been “piloted by men whose bravery surpasses any other action by either side that day”.

Nigel Pumphrey’s torpedo boats proved no more adept at penetrating the screen of destroyers and E-boats. Three craft got their ‘fish’ away – at maximum range, 3,500-4,000 yards. Not one torpedo hit home.

“At this juncture a large waterspout appeared close to us, then another and another,” recalled Reg Mitchell on MTB48. The boat was being engaged by the German destroyer Friedrich Ihn, bearing down rapidly on the small British force. “We turned around and put our feet down to get out of it,” said Mitchell. The craft made for the shallows of the Goodwin Sands. The destroyer could not follow them there.

The coastal batteries, the motor torpedo boats, the six antiquated Swordfish had all failed. Cerberus was through the gates of Hell – but the ships were not yet safe.

Aboard the Prinz Eugen, the Matrosen – matelots – took comfort that the weather gods were on their side. “The weather grew worse,” Paul Schmalenbach recalled. “Our native North Sea greeted us with light rain and rough seas. On top of that, visibility became ever worse; the cloud ceiling dropped to just a few hundred metres.”

Edgar Lee and Brian Rose pitched up and down in their dinghy for a good 90 minutes. The action had long since passed – the Germans were approaching the Scheldt estuary, a good 50 miles away. With the Channel devoid of the foe, Lee fired two distress signals and awaited rescue from motor torpedo boats, be they German or British – whichever came first. “Better a PoW than float aboat in this oggin for much longer.”

So far it had been a useful, if otherwise uneventful, Thursday off Orfordness for the ships of the 16th Destroyer Flotilla. As HMS Worcester prepared to take over target-towing duties, the flotilla leader, HMS Campbell, received a terse signal: Enemy cruisers passing Boulogne, speed about 20 knots. Proceed in execution of previous orders.

With a combined age of nearly 120 years, the five ships – Campbell, Vivacious, Worcester, Whitshed and Mackay – were better suited to convoy duties than chasing German capital ships.

Flotilla commander Mark Pizey chose to intercept the enemy off the Hook of Holland and signalled his intentions to the rest of his destroyers.

Aboard HMS Worcester, a sub lieutenant hurried down from the bridge with news for his shipmates. “Roll on my VC! We are to intercept the pocket battleships!”

A torpedo boat had sighted Edgar Lee’s flare and closed in on his dinghy. Was it friend or foe? Lee wondered. “Then I saw it was flying the Jolly Roger and realised that no German would have that sense of humour.”

So far, Otto Ciliax’s ships had run the gauntlet unscathed. There were reports of half a dozen warships steaming through the North Sea to intercept – but so far there was no sight of them, nor of fresh waves of Swordfish. The Matrosen saw only the deepening gloom of a waning February day.

And so with no foe evident, the shock was all the greater when the Scharnhorst was rocked by a tremendous explosion. The battle-cruiser shuddered to a halt having run over a mine previously laid by the RAF.

Damage-control parties minimised the flooding to a couple of compartments and within half an hour had restored power to the Schlachtschiff.

But by then Scharnhorst was no longer flagship. Ciliax had abandoned her with his staff, transferring to a destroyer. Not a few members of the ship’s company thought his actions precipitous.

While the Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen continued on their way, Scharnhorst sat dead in the water, and Mark Pizey’s aged destroyers made best speed to intercept Ciliax’s ships, the second act of the Channel battle was already under way.

After its initially lacklustre response to the German breakout, by mid-afternoon the RAF was throwing bombers at the enemy as it hastened up the Belgian coast.

More than 250 aircraft took off to attack the trio – Wellingtons and Manchesters (forerunner of the more successful Lancaster), four-engined Halifaxes, twin-engined Beaufort torpedo bombers. And while it had failed to provide adequate cover for Eugene Esmonde’s ill-fated Swordfish, the RAF sent up fighters en masse – nearly 400 in all – to shield the bombers.

For all this effort, fewer than 40 actually found the Germans. The men on the Prinz Eugen tried to follow the aerial battle. “Flashes of light and explosive clouds painted the grey sky with colour,” Paul Schmalenbach recalled. Two fighters chasing a Wellington bomber here. A Messerschmitt and Spitfire locked in a dance of death there. A four-engined bomber plunged out of the sky. The ship’s flak only opened fire when there was no risk to German aircraft or ships.

HMS Campbell had negotiated North Sea minefields and survived bombing raids first from a Junkers 88, then from an RAF Hampden (neither hit), before a flight of Messerschmitts circled hesitantly a couple of times before departing. “It was becoming increasingly apparent that the sense of confusion was not all one-sided,” recalled telegraphist John Keith.

His captain was “beginning to give up hope” of encountering the Germans until, a little after 3.15pm, a couple of large echoes appeared on the radar screen 20,000 yards – more than 11 miles – away. The two large blips – Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen – were soon joined by smaller echoes, their escorting destroyers.

It was another dozen minutes before the flotilla could physically see the German ships. The British destroyers increased speed and closed on the foe.

Just above the waves Messerschmitts grappled with Beaufort torpedo bombers while higher up there was a tangle of Dorniers, Me110s, Hampdens, Spitfires, the occasional Halifax bomber and twin-engined Wellingtons.

The Luftwaffe thought the destroyers below friendly and fired recognition signals, while the RAF crews were convinced the flotilla was German.

The only people ignorant of this general mêlée were the crews of the Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen. Their guns remained silent – but not for long.

“I could clearly see the vivid flashes of their guns as they fired,” John Keith remembered. “Great columns of water erupted into the air off either bow and large projectiles roared close overhead.” To the young seaman these passing shells sounded like express trains.

Aboard Worcester, pom-pom officer S/Lt Bill Wedge could make out “dark shapes in the misty distance”. Despite green seas crashing over the forecastle and stern, the veteran destroyer’s main 4.7in guns opened up, their crews up to their knees at times in water.

It was now around 3.40pm. The charge of the destroyers had closed the range to under 3,500 yards – possibly as close as 2,400. When an unexploded shell crashed into the sea “like a porpoise” just ahead of the Campbell, Capt Pizey took it as the signal to fire his torpedoes and turn about.

Pizey’s ships fired their ‘fish’ and turned about. All except the Worcester. She continued “for what seemed an age” until the ‘fish’ were finally fired from her tubes – just 2,000 yards from the Germans.

She paid a heavy price for her death ride. For ten minutes she was straddled and hit repeatedly. Four salvos in succession struck her. Two boiler rooms were knocked out and the Worcester lay dead in the water. Her captain, Lt Cdr Ernest ‘Dreamy’ Coates, gave the order ‘prepare to abandon ship’. In the confusion of battle, and with many of his men suffering from concussion, his instructions were misheard or misinterpreted. Many men – the wounded and uninjured – took to Carley Floats and drifted out into the North Sea.

Above, a Junkers 88 circled but did not attack the stricken Worcester. The RAF did, trying to torpedo her.

Below, the surgeon and sick bay attendants tended to the wounded, while the engineers finally restored some power and began to make for home.

As Worcester got under way again, more shapes out of the growing gloom – but not German destroyers, rather British. Campbell and Vivacious had returned and promptly set about rescuing the men in the water.

The motor boat which had plucked Edgar Lee and Brian Rose from the Channel safely delivered them to Dover, where the pilot was promptly whisked off to hospital. As for the 20-year-old Lee, he was taken to Admiral Ramsay’s headquarters to “thaw out”. He was laid on a stretcher and thrust into a tunnel-shaped piece of corrugated iron with a row of 100-watt lightbulbs fixed to it. It was, Lee remembered, “a wonderful piece of kit, absolutely basic but very effective”. Once warmed up, he was shown into Ramsay’s office. For the next hour, the young aviator and the experienced admiral were closeted. “This man was surrounded by absolute mayhem on his doorstep and yet he could give time to put my mind at rest,” Lee recalled 65 years later. “I thought that was the sign of a really great man.”

Edgar Lee’s report of the action – his battle lasted no more than half an hour – left Bertram Ramsay profoundly depressed. Had he known only one squadron of fighters, not the promised five, was available as escort for the Swordfish he “would have told Lt Cdr Esmonde to remain on the ground. Indeed, I would have forbidden the flight as an order.”

In the North Sea murk, the Prinz Eugen had lost sight of the Gneisenau, which was now leading the charge up the Channel. Visibility was so poor that her crew could not see the torpedo and light bombers trying to attack the cruiser, only hear their engines. The closest the bombs fell was 50 metres, but one crewman was killed as a plane’s machine-guns raked the ship. The flak responded with a hit to the aircraft’s tailplane. It plunged into the sea as the last flicker of daylight was expunged this Thursday. Darkness once again enveloped the fleeing German ships.

HMS Worcester broke down once more as she struggled back to Harwich. Her engineers again performed miracles and the destroyer limped into port doing nine knots – proudly turning down an offer of assistance from another destroyer.

Like Scharnhorst before her, Gneisenau was suddenly brought to a halt off the Dutch island of Terschelling. A mine, laid by the RAF earlier that day, detonated, ripping a hole near her stern. The damage, unlike Scharnhorst, was relatively superficial. After half an hour’s makeshift repairs, she resumed her journey to the German Bight.

Her older sister was not so fortunate. Lagging behind the rest of the Cerberus force thanks to her earlier mishap, the lucky Scharnhorst was now making 27 knots, racing up a channel between minefields off the Dutch coast. The speed troubled navigator Helmuth Gießler – were another accident to befall the battle-cruiser, it might prove fatal. He suggested slowing down to his captain. Kurt Hoffmann refused. He accepted the risks. “Only God and courage can help us now,” he told Gießler.

Helmuth Gießler was right. As Scharnhorst passed Terschelling, she too hit an aerial mine. The engines failed immediately. So too the lights as the North Sea gushed into engine spaces and the main generator compartment. The battle-cruiser began to drift towards the Dutch shore.

Once again the engineers came to the lucky Scharnhorst’s rescue; in little more than half an hour they had restored power. At 12 knots, she crept through the darkness up the Frisian coast.

Edgar Lee was driven the 20 miles back to Manston from Ramsay’s headquarters. He was now the senior surviving officer of 825 Naval Air Squadron. To him fell the solemn task of sorting out the personal effects of his comrades for their families. With the duty done, he paid a call on the station commander, then headed to the mess for dinner. A deadly hush descended on the dining hall.

As the Scharnhorst slowly made for Wilhelmshaven and Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen steamed for the mouth of the Elbe, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound – the man who had insisted on the suicidal Swordfish attack – was put through to No.10. In his time as First Sea Lord, Pound had informed his premier of good news – the destruction of the Bismarck – but more often than not, bad – the sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse was a particular low point. Now, at 1am on Friday February 13, he had bad tidings once more for Churchill. “I’m afraid sir I must report that the enemy battle-cruisers should by now have reached the safety of home waters.”

There was a long, silent pause on the other end of the line before the prime minster spoke. “Why?” he asked, then slammed the phone down.

The German ships had indeed escaped – but they had not yet reached home waters. It was 7am on Friday before Prinz Eugen and Gneisenau arrived in the Elbe estuary. They did so with the feeling, Paul Schmalenbach wrote triumphantly, “of having given our toughest enemy at sea a hefty slap in the face by sailing past his front door – opening on to what he alone claims is called the ‘English’ Channel – without him being able to impede us.”

When the damaged Scharnhorst finally limped into Wilhelmshaven, her sides were lined with ecstatic sailors. When the gangways were across, senior naval and Luftwaffe commanders were invited aboard to review the operation. They deemed it a complete success: the breakout, Adolf Galland wrote, had been “a military sensation of the first order”, and his aerial umbrella “a great and impressive military victory”. His fighters and the ships’ flak had downed more than 40 enemy aircraft for the loss of 17 on the German side. Eleven aircrew and 13 Matrosen were dead, and a solitary picket boat (a trawler) had been sunk.

In Berlin, Adolf Hitler was hosting his Norwegian puppet, Vidkun Quisling, for lunch. Just how much of a puppet Quisling was Hitler confided afterwards to Joseph Goebbels. The Norwegian had great plans: to forge a new army and navy and defend his country’s shores. One day, Quisling argued, his country would be free of German troops, yet still stand at Germany’s side. Hitler’s responses were lukewarm and evasive.

The Führer was rather more forthcoming on the subject of the warships’ breakout. He was “very happy” with the outcome of the operation. “Our stock has risen considerably – while that of the British has fallen correspondingly.” With the fall of Singapore imminent perhaps, Hitler mused, Churchill might fall.

Perhaps he might, for the British media bayed for blood when news of the German success reached London. Harking back to the Armada, the editorial in The Times fumed:

Vice Admiral Ciliax has succeeded where the Duke of Sidonia failed. Nothing more mortifying to the pride of sea power has happened in Home Waters since the 17th Century.

Of course, the Brest flotilla should not have escaped. The British response – exactly as Hitler predicted – had been sluggish, disorganised, belated. Even in this third year of war, liaison between the Air Force and Navy was poor, while the RAF ill-equipped and certainly ill-trained for attacking “fast-moving warships by day”. And while Winston Churchill might have snapped in private at Dudley Pound, publicly he defended his Navy. “Where, it is asked, were all the rest of our flotillas?” he told Parliament. “The answer is that they were – and are – out on the approaches from the Atlantic, convoying the food and munitions from the United States without which we cannot live.”

In short, the Navy had too many commitments – and too few ships.

The Germans’ initial self-congratulation quickly faded. The Brest flotilla never did deploy to Norway as intended; damage to Scharnhorst was so bad she would not be fit for duties until the beginning of the following year. Six days before the end of 1943, the Royal Navy sank her off the North Cape.

As for her sister, her damage was largely superficial. By February 26, she was ready to begin trials before deploying to Scandinavia a week later. That night Bomber Command visited Kiel. A bomb penetrated Gneisenau’s armoured deck on her bow and ignited shell propellant. Crew succeeded in flooding most of the magazine to prevent the entire ship exploding. The resulting blast was sufficient to blow a turret off, wreck the bow and kill more than 100 sailors. Never again did the Gneisenau sail as an operational warship.

Save for one sailor killed, the Prinz Eugen had come through Cerberus unscathed. Engineer Erich Kettermann was laid to rest with full military honours in the small cemetery at Brunsbüttel by the entrance to the Kiel Canal. When the ship’s company returned aboard the cruiser, the Fleet Commander-in-Chief was waiting for the captain. Why hadn’t Helmuth Brinkmann stayed with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau when they hit mines, but continued on alone? Brinkmann pointed out that his was the only ship to return to Germany undamaged – as ordered. Schniewind smiled and offered the captain a glass of champagne.

Prinz Eugen did not remain undamaged for long. Sent to Norway with the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and half a dozen destroyers, she was torpedoed by submarine HMS Trident off Trondheim on February 23. The explosion ripped off her stern. Though eventually repaired, the cruiser spent the rest of her career under the swastika as a training ship in the Baltic and floating gunnery platform supporting the crumbling Eastern Front.

And so like so many feats of German arms in the 20th Century’s second global conflagration, the Channel Dash was a tactical triumph but strategic defeat. “The Battle of the Atlantic, as far as our surface forces were concerned, was practically over,” Erich Raeder lamented. Never again would major German warships strike into Atlantic Ocean.

In early April the Channel finally gave up Eugene Esmonde’s body. Still wearing his life jacket, he was washed ashore near the Medway estuary. By then his name was immortal. George VI had already conferred the nation’s highest honour, posthumously, on the squadron commander. The recommendation had come from Bertram Ramsay.

Such bravery as was his is in keeping with the highest naval traditions and will remain through generations to come a stirring memory.